| This conservation resource was created by Brennan Guse, Sean Downing, Joey Zhang, Hengameh Rahmati, and Chang Brian. |

How Street Trees Can Save Our Cities

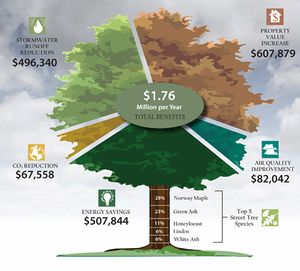

Cities around the world are looking for ways to improve the livability of their cities and street trees are a common and important remedy for urban planning departments. The initial appeal of street trees is the beauty they can bring to an area that could be devoid of non-concrete materials. However, street trees can also serve a community beyond the aesthetics of greenery within an urban space, as agents of more practical contributions to the health of the city. Street trees are relatively inexpensive solutions to the common problems of large urban areas, like air pollution, overburdened sewer systems, and the health of the people living and working in it. Street trees are often a good investment for urban planning departments for they give a great value to a city while the cost to maintain them can be a fraction of the benefits.

Urban forestry more broadly is the action of caring for either a single tree or large group of foliage, often done by a civil government however maintenance can also come from private individuals. The entire population of trees in a city is an urban ecosystem and it is the job of its citizens to ensure the trees' survival. In this case street trees fall under the category of urban forestry and are quite an integral part to the health of a city's ecosystem. This page is devoted to the analysis of how street trees can contribute to the environmental, social, and economic well being of a city. Street trees can improve aspects of city life like air quality, biodiversity, and various beneficial health outcomes. Cities can improve their quality of life by adding trees and other foliage along the side of their roads.

Air Quality

Urban environments are increasingly suffering from bad air quality and smog. Planting trees remains one of the cheapest and most effective ways of drawing access carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.[1] In fact, trees in street proximity absorb 9 times more pollutants than more distant trees, converting harmful gasses back into oxygen. [2] Street Trees can improve air quality by intercepting and absorbing particulate pollution at street level, [3] reducing urban ozone levels by lowering air temperatures through transpiration, removing air pollutants through surface deposition, and reducing building temperatures. [4] Street trees remove pollutants such as: ozone, particulate matter less than 10 μm, nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide and carbon monoxide. [5] The pollutants most commonly removed by urban trees in US cities are ozone and particulate matter. [4] Removal values vary among cities according to tree cover, pollution concentration, length of in-leaf season, precipitation levels and factors that affect tree transpiration and deposition velocities. [5] Species such as whilst ash, alder and birch have some of the greatest air quality benefits, especially during hot weather events. [6] Overall, the average Canadian urban tree is estimated to remove about 200 kg of carbon over an 80-year period. [7]

Climate

Urban environments exhibit a fundamentally different climate from those found in nearby rural areas. [8] Urban areas experience distinctive solar radiation, air quality, rainfall patterns, wind speeds, humidity and temperatures. [9] These microclimatic elements are influenced by the built environment, the local topography and the surrounding natural environment. Urban areas generally have higher temperatures due to the urban heat island affect, [10] higher levels of precipitation due to higher particulate concentrations, [11] and increased flooding due to loss of canopy cover and abundant impermeable surfaces. The urban microclimate is also influenced on a smaller scale by the built environment, such as urban density, shade from buildings, and the type and abundance of urban vegetation. [9]

Street trees can improve the urban environment for city residents. For example, street trees reduce the urban heat island effect by providing shade. [12] In addition, evapotranspiration from street trees reduces air temperature through the conversion of sensible to latent heat and by adding water vapour to the air. [9] In cooler seasons, street trees can reduce space heating needs by decreasing wind speeds and thus cold air infiltration into buildings. [12] A study in London shows that temperatures can be up to 10C lower under the shade of trees than in the open street. This is important as temperatures continue to increase with climate change.

Hydrology

Street trees act as natural water filters and help significantly slow the movement of storm water, which lowers total runoff volume, soil erosion and flooding. [13] When compared to natural forested environments, urban environments have decreased interception of precipitation from canopies and abundant impermeable surfaces, leading to higher flooding risk in urban environments. During peak precipitation events, water flows over the surface of the ground instead of infiltrating into it, creating high levels of surface runoff and flow through stormwater systems. [14] Street trees and the permeable soil in which they grow, can help regulate surface runoff by intercepting rainfall, evapotranspiring, and increasing soil infiltration rates. [15][16] This also reduces the amount of soil erosion in nearby rivers. One study has estimated that for every 5% increase in tree cover area, run-off is reduced by 2%. [17]

Wildlife

Street trees provide nesting sites for birds and support a wide range of insects that are an important food source for birds and other wildlife. [18] Street trees that bear berries are also a direct source of food for many bird species. Pollinators also benefit from street trees, this is because trees provide nesting sites, pollen and nectar. [19] Pollinators may use tree leaves as nesting materials and the tree canopy as a resting place. [19] In an urban setting, street trees create linear corridors of habitat, connecting otherwise isolated areas to each other and out to rural surroundings. [18] This is important for wildlife migration and for connecting natural areas. Street trees and other vegetation can also play an important role in reducing noise through reflecting and absorbing sound energy. Field tests show apparent loudness reduced by 50% by wide belts of trees and soft ground. [20] This is important as many animal species choose to make habitats in quieter locations. Overall, trees provide habitat, food, and protection, to plants and animals, and increase urban biodiversity. [21]

The City of Toronto

The city of Toronto is taking great efforts to increase its canopy cover. Toronto’s mayor John Tory, who has planted 40,000 trees since his election victory in 2014, has promised 3.8 million more over the next decade. [22] The City of Toronto owns a portion of land between roadways and private property, known as the public road allowance. Urban Forestry plants and maintains trees on this land to help grow Toronto's urban forest and to reach the City's goal of increasing the tree canopy to 40 per cent. [23] Toronto currently has an estimated 26.6 - 28% tree canopy cover, representing 10.2 million trees. [23] Of those trees 600 000 are estimated to be street trees. [23] Overall, in North America and internationally, there is a growing body of research that supports the importance of maintaining healthy, sustainable urban forests.

Introduction

Street trees can improve the livability of cities in many different ways. In its lifetime a tree provides us with many benefits. In recent years the idea of street trees have became a popular idea, therefore more people are recognizing the need for it. The street trees have to be the default design for our streets. Trees have great social impacts for our cities and their citizens. Trees can be seen as a symbol of nature in our urban societies. As global warming has became an important issue, the positive effect of trees have been more widely known.

Problems caused by street trees

There can be some problems caused by street trees. These problems can include: positioning of the trees to allow required sight at intersections and driveways, blocking the street luminaries, damaging the concrete sidewalks, affecting the utility lines both above or below the ground. [24] . Even though there can be some minor problems caused by the street tree, these problems can be easily solved by designers.

Benifits gained from street trees

Reduce traffic speed

One great thing about the street trees is that they can "reduce the urban traffic speeds" [25]; by forming walls on the sides of the street. In other words by forming edges on the sides of streets, and by doing so, they can help drivers manage their speed. Especially when comparing this design to the asphalted streets it is highly efficient to have trees. This is because asphalt encourages speeding whereas, trees have a" traffic calming effect" [24]. Therefore, street trees increase the street safety by reducing the car crash or reducing the severity of the crashes.

Improve sidewalk quality

Having safer streets leads to creation of safer sidewalks. The trees can act as seeable walls separating the sidewalks. Thus, sense of security increases and psychologically people will feel better by going for a walk in a more pleasant walking environment. Which will increase walking, social interactions, talking, caring for places, and also sense of ownership of neighborhoods and streets. This feeling might be because people think that they have their own space in the street. Street trees also have positive effects on our health such as skin protection. These trees can protect us against rain, sun, and heat. The trees can act as a canopy blocking most of the sun and rain. Also there can be temperature differences when walking under these tree canopies.

Aesthetic

A great fact about the trees is that since there is a great variety of them, there will be a tree that can be used in any climate, thus there is no limitation to having street trees.The beauty that trees bring to our streets is very valuable. Trees can change parking, walls, and in general the overall look of the city into a more beautiful city. In other words, it can filter or cover any feature in the street that can be seen as a visual pollution. For example, a lawn can make a parking area both beautiful and also allow us to use it in different ways such as water storage, spray zone, and a transition for driveway elevations. Also Properly designed tree wells that are placed in the right area, make "a compelling line of green, hiding much of the excess asphalt needed for parking"[26]

Provide comfortable environment

Besides the tree wells, curb extensions can be used which are good for seating areas or corner placement. These seating areas can make the sidewalks a more pleasant area for the pedestrians. It can also be seen as providing a good way for elders and people who have difficulty walking to be able to still walk and they can seat down when they get tired, rather than staying at home and not walking.

Connection to nature

Street trees can bring about the connection to nature. We as humans need to be connected to nature in order to be happier and healthier. Thus these street trees can provide a great connection for us. To look from another perspective, these "street trees provide a canopy, root structure and setting for important insect and bacterial life below the surface"[27]. The insects and bacteria are also an important form of life that are essential for living.

Positive psychological effect

Interestingly, these trees can have an improving effect on human's emotional and psychological health. Since humans can be impacted by what they see, seeing a beautiful natural, green scenery can improve their health. It can also decrease the blood pressure, because as mentioned by Kathlene Wolf, " trees have a calming and healing effect". Due to the same calming effect, researchers have shown that street trees can decrease road rage. It has been shown that the drivers' road rage decreases in green areas.

Prevention of water run-off

Furthermore, trees can cause " less drainage infrastructure". Since they usually absorb the first 30% which will be evaporated back to the atmosphere. Another 30% of the precipitation is going to be absorbed in their roots. "Some of this water also naturally percolates into the ground water and aquifer" [28] Thus the "storm water run-off and flooding potential" [24]can be decreased.

Everything in the world has value to it. Trees can have a surprising amount of economic value to them, whether towards the city, the residents, or the environment. Although there are multiple approaches towards determining the economic values of trees and green vegetation, they can be summarized to be municipal and commercial arboriculture. Trees can be analyzed individually or in groups, as woodlands or forests. Their values can be valued by either residue, or their wood value. Trees have a marketplace value, whether being street trees, Christmas trees, yard trees, etc. there have been numerous amounts of studies done based on the percentage of economic value trees have in contribution towards property"[29].

Individual Trees

Trees economic values should be viewed as an asset that it has, in other words, potential benefits, and liabilities. Therefore, planting a tree can be viewed as an investment, although the benefits do not come in the form of money very often. The value of a single tree is determined through the following categories: maintenance costs, wood products and residues values, preservation costs, replacement costs, and contribution to value of property"[30].

City Assets

Trees, just like any other city asset, have a record for their appraised valuation kept by the city government"[31]. However, there is a difference between trees and other city assets such as infrastructure, lampposts, or vehicles. Trees gain value over time, meaning they have an increase in economic worth as time passes. Other assets, lose value over time, as they wear out and become unusable or behind in technology.

“Street trees increase the value of adjoining properties. Donovan and Butry (2010) found street trees in front of homes added $8,870 to the sale price, or 3.4% to the median $259,900 property value in Portland, Oregon… Homes with street trees also sold faster, with the average time on the market reduced by 1.7 days. Street trees provided $1.35 billion to property values in Portland, adding $15.3 million annually in tax revenue”"[32].

Maintenance Costs

Lifetime investment of a tree needs to be included when calculating the net value. A city tree’s lifespan undergoes three stages in terms of work done by humans: planting/establishment, periodic maintenance, and removal. Proper procedures are critical when establishing a tree, as improper establishment can lead to more frequent maintenance requirements, special care, and even early removal, causing the tree to not be able to fulfill its full-intended economic value"[33]. A tree can have growth in economic value by the following procedures. Investment in the lifetime of a tree can cost $1000, for example. If interest rates, about 6%, for example, were to be applied to each step of establishment, maintenance, such as pruning, and finally removal after 40 years, the economic value of the tree after 40 years will be much higher than what was invested, at around $4000. Net benefits will be approximately $2000.

Benefits to Cost Approach

(B/C) looks weighs the benefits to the costs of a tree during its lifespan. Benefits can include conservation of energy, improvement of air quality, CO2 reductions, storm protection, soil preservation, and water management. Costs of a tree are maintaining the tree so that it remains safe and appealing to the citizens"[34].

Wood Products or Residue

Nowadays in already economically developed countries, chopping down city trees for the use of fire wood or wood products is certainly rare and even illegal in most places. City government usually oppose cutting down a healthy growing tree. Although a city can have a patch of secondary artificially grown forest to accompany the request for wood by sawmills and factories"[35].

Council of Tree and Landscape Appraisers’ Valuation

The International Society of Arboriculture (ISA) published the Council of Tree and Landscape Appraisers (CTLA)’ Guide for Plant Appraisal. It describes the widely used methods of tree and landscape appraisal in North America[36].

City officials, especially those in the urban planning departments, must recognize the benefits street trees can give to their local environment. By adding trees to the side of the road a city can encourage more wildlife, like birds and insects, to migrate to the city, therefore, pollinating more and increasing the biodiversity. Human residents will also benefit for not only do people find trees aesthetically pleasing but it is better for our respiratory health when trees are more abundant in an urban area. Street trees reduce the smog and pollutants in our air that city life produces constantly. Cities can even benefit economically from street trees, which cost them very little to start. The City of Vancouver takes action against the loss of urban forest - in their Urban Forest Strategy Plan, the city plans to plant 150,000 trees by 2020.

The opponents of the proliferation of street trees are merely apathetic urban planning departments and city officials. Rarely are people against the installation of street trees but sometimes city officials may become ignorant of their benefits. Street trees will thrive in cities when their respective planning boards recognize the good street trees can do for the character, environment, and economy of a city.

In the future, street trees should be considered an integral part of any new design effort by a city in recognition of their benefits. Just like the environment and housing prices, street trees are an important factor in improving the quality of life in our urban spaces. This means cities must consider street trees as solutions to their problems and analyze their impact when making new policy decisions.

- ↑ Keep Indianapolis Beautiful. (2017). Urban Trees. Retrieved March 26, 2017

- ↑ Burden, D. (2006). Urban Street Trees. Retrieved March 26, 2017, from http://www.walkable.org/download/22_benefits.pdf

- ↑ Heidt, V., & Neef, M. (2008). Benefits of Urban Green Space for Improving Urban Climate. In M. Carreiro, Y. Song, & J. Wu (Eds.), Ecology, Planning and Management of Urban Forests (pp. 84–96). New York: Springer.

- ↑ 4.04.1 Nowak, D. J., Civerolo, K. L., Trivikrama Rao, S., Gopal Sistla, Luley, C. J., & E. Crane, D. (2000). A modeling study of the impact of urban trees on ozone. Atmospheric Environment, 34, 1601–1613. doi:10.1016/S1352- 2310(99)00394-5

- ↑ 5.05.1 Nesbitt, N. H. L., Cowan, S. B. J., Cheng, Z. C., PI, S. S., & Neuvonen, J. (2015). The Social and Economic Values of Canada’s Urban Forests: A National Synthesis, 23.

- ↑ Hastie, C. (2003). The Benefits of Urban Trees. Retrieved March 26, 2017, from https://www.naturewithin.info/UF/TreeBenefitsUK.pdf

- ↑ Urban tree benefits. (2017, January 13). Retrieved March 26, 2017, from https://www.kelowna.ca/parks-recreation/urban-trees-wildlife/urban-trees-their-benefits

- ↑ Nesbitt, N. H. L., Cowan, S. B. J., Cheng, Z. C., PI, S. S., & Neuvonen, J. (2015) The Social and Economic Values of Canada’s Urban Forests: A National Synthesis, 23.

- ↑ 9.09.19.2 Heidt, V., & Neef, M. (2008). Benefits of Urban Green Space for Improving Urban Climate. In M. Carreiro, Y. Song, & J. Wu (Eds.), Ecology, Planning and Management of Urban Forests (pp. 84–96). New York: Springer.

- ↑ Oke, T. R. (1973). City size and the urban heat island. Atmospheric Environment, 14, 769–779.

- ↑ Bonan, G. B. (2002). Ecological Climatology: Concepts and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 12.012.1 Dwyer, JF, McPherson, EG, Schroeder, HW and Rowntree, R, 1992, Assessing the Benefits and Costs of the Urban Forest, [in] Journal of Arboriculture 18(5), pp 227 - 234.

- ↑ Benefits of Urban Trees. (2014). Retrieved March 26, 2017, from http://www.southernforests.org/urban/benefits-of-urban-trees

- ↑ Nesbitt, N. H. L., Cowan, S. B. J., Cheng, Z. C., PI, S. S., & Neuvonen, J. (2015). The Social and Economic Values of Canada’s Urban Forests: A National Synthesis, 23.

- ↑ Asadian, Y. (2010). Rainfall interception in an urban environment (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from the https://circle.ubc.ca/

- ↑ Konijnendijk, C. C. (2013). Benefits of Urban Parks - A systematic review. International Federation of Parks and Recreation Administration, (January).

- ↑ Hastie, C. (2003). The Benefits of Urban Trees. Retrieved March 26, 2017, from https://www.naturewithin.info/UF/TreeBenefitsUK.pdf

- ↑ 18.018.1 Hastie, C. (2003). The Benefits of Urban Trees. Retrieved March 26, 2017, from https://www.naturewithin.info/UF/TreeBenefitsUK.pdf

- ↑ 19.019.1 Toronto, C. O. (n.d.). Street Tree Planting. Retrieved March 26, 2017, from http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly vgnextoid=a7643dfce3a0d410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

- ↑ Dwyer, JF, McPherson, EG, Schroeder, HW and Rowntree, R, 1992, Assessing the Benefits and Costs of the Urban Forest, [in] Journal of Arboriculture 18(5), pp 227 - 234.

- ↑ Benefits of Urban Trees. (2014). Retrieved March 26, 2017, from http://www.southernforests.org/urban/benefits-of-urban-trees

- ↑ Barkham, P. (2015, August 15). Introducing 'treeconomics': how street trees can save our cities. Retrieved March 26, 2017, from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/aug/15/treeconomics-street-trees-cities-sheffield-itree

- ↑ 23.023.123.2 Toronto, C. O. (n.d.). Street Tree Planting. Retrieved March 26, 2017, from http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=a7643dfce3a0d410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

- ↑ 24.024.124.2 Studio, T. W. (n.d.). Benefits of Urban Forests. Retrieved April 06, 2017, from https://treecanada.ca/en/programs/urban-forests/benefits/

- ↑ Beckley, T.M., and Burkosky, T.M. 1999. Social indicator approaches to assessing and monitoring forest community sustainability. Can. For. Serv. North. For. Res. Cent. Inf. Rep. NOR-X- 360.

- ↑ Kaufman, H.F., and Kaufman, L.C. 1946. Toward the stabilization and enrichment of a forest community: the Montana study. University of Montana, Missoula, Mont.

- ↑ Bliss, J., Bailer, C., Howze, G., and Teeter, L. 1992. Timber dependency in the American south. Presented at the 8th World Congress for Rural Sociology, University Park, Pennsylvania, 16–19 August 1992.

- ↑ Parkins, J., Stedman, R., and Beckley, T. 2003. Forest sector dependence and community well being: a structural equation model for New Brunswick and British Columbia. Rural Sociol. 68(4): 554–572

- ↑ Miller, R., Hauer, R., Werner, L. 2015. Urban Forestry: Planning and Managing Urban Greenspace, p. 114. Waveland Press Inc, Illinois. ISBN 1478606371.

- ↑ Miller, R., Hauer, R., Werner, L. 2015. Urban Forestry: Planning and Managing Urban Greenspace, p. 114. Waveland Press Inc, Illinois. ISBN 1478606371.

- ↑ Miller, R., Hauer, R., Werner, L. 2015. Urban Forestry: Planning and Managing Urban Greenspace, p. 114 - 115. Waveland Press Inc, Illinois. ISBN 1478606371.

- ↑ Miller, R., Hauer, R., Werner, L. 2015. Urban Forestry: Planning and Managing Urban Greenspace, p. 114 -115. Waveland Press Inc, Illinois. ISBN 1478606371.

- ↑ Miller, R., Hauer, R., Werner, L. 2015. Urban Forestry: Planning and Managing Urban Greenspace, p. 115 -116. Waveland Press Inc, Illinois. ISBN 1478606371.

- ↑ Miller, R., Hauer, R., Werner, L. 2015. Urban Forestry: Planning and Managing Urban Greenspace, p. 116. Waveland Press Inc, Illinois. ISBN 1478606371.

- ↑ Miller, R., Hauer, R., Werner, L. 2015. Urban Forestry: Planning and Managing Urban Greenspace, p. 116 - 119. Waveland Press Inc, Illinois. ISBN 1478606371.

- ↑ Miller, R., Hauer, R., Werner, L. 2015. Urban Forestry: Planning and Managing Urban Greenspace, p. 119 -124. Waveland Press Inc, Illinois. ISBN 1478606371.

Post image: Tree-lined road. I, Parpan05 CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons