Ban Thung Yao village is located in the Lamphun province of Northern Thailand. Members of the community have been managing the forests since their settlement in 1915. They depend on the forest to extract both timber and non-timber based products such as mushrooms, bamboo shoots, medicinal plants and herbs. The women in Ban Thing Yao community play a significant role in securing the local people’s rights and their heritage. They contribute to managing the forest by patrolling, maintaining the nursery, keeping records of violators, and organizing local knowledge-sharing events. When the Royal Forest Department announced Ban Thung Yao community forest as a National Park in 1987, the women’s group in the community expressed their displeasure the strongest.

Northern Thailand has a population of 10.5 million, with 17 million hectares of land. The area of our case study, the Ban Thung Yao Village is located in this region. Five mountain ranges “run north-south with elevations ranging between 550 and 2,500m and valley floors varying from 200 to 500m above sea level”[1]. There is 1,000 to 4,000 millimeters (mm) of rainfall per year and two distinct dry and rainy seasons. During the dry season, the temperature tops out at 40°C. The median temperature is 25°C. During the cold dry season, the lowest temperature is 0°C. Thailand has a population of 69 million people, with a 0.4% growth rate and 51 million of hectares of land. The population density is 123 persons/km2. 80% of the population currently lives in rural areas, however we have seen an increase towards urbanization in recent decades. In 1965, “only 13 percent of the population lived in urban areas, with 23 percent in 1990, declining to 21 percent in 2000”[2].

There are two main types of forest in this region, evergreen and deciduous, with variations of altitude, soil, rainfall and other factors in each type. In deciduous forests, there are “dry dipterocarp, dry mixed deciduous, and moist mixed deciduous” [1]. In evergreen forests, there are “lower montane, coniferous, and dry evergreen”[1]. The most valued type of forest is the mixed deciduous forest, as this type contains teak, a hardwood species which is highly demanded. Over 70% of Thai people are involved in agriculture related occupations. Other main areas of work include manufacturing and service industries. To obtain agricultural supplies, most people in local communities go to river valleys to collect them. The Chiang Mai valley has been the most successful in Northern Thailand, which is 124 kilometres from Ban Thung Yao community.

The highest level of land ownership in Thailand is the Chanode Thidin. The person in possession of this certificate can sell, transfer, or mortgage the property. In urban areas, full title deeds are more common, which serves the same purpose as the Chanode Thidin.The most prevalent tenure certificates in Thailand include the NS.3 and NS.3.A. Holders with these certificates have the right to farm the land and use them as collateral to borrow money. The next most prevalent tenure certificates include PBT.5and PBT.6certificates. PBT certificates land tax receipts but do not give the holder land title. However, the land can be farmed and residences can be built, but cannot be sold or used as loan collateral. The land can be taken away by the Royal Forest Department’s Forest Village Programmeat any point for reforestation or reallocation purposes. The purpose of PBT certificates is to give the farmers of the local community a feeling of ownership so that they now are motivated to spend their time to work on the land and to stay in the area. The land remains apart of the state, in this case. It is estimated that approximately 90% of property owners in Thailand do not have legal ownership to the property. Land title is primarily held by men, whether it be the NS or the PBT certificates.

The First and Second National Economic and Social Development Plan (NESDP) (1961-1971) was implemented to increase economic growth through building roads, electricity, and water supply networks. Although Thailand as a country has prospered economically, income distribution and the quality of life of local people have declined during the early 1970’s. The Third National Economic and Social Development Plan (1972-1976) was needed to emphasise on “social development, reduction of the population growth rate, and income distribution” (p.7). Amidst the Fourth Plan period (1977-1981), the future plans of the government were uncertain, as a result, there was an economic downturn. As a result, the Fifth and Sixth Plans (1982-1991) focused on economic stability and bringing the population out of poverty. The Seventh Plan (1992-1996) wanted to promote sustainable development especially in economic growth and stability, “income distribution, developing human resources, and enhancing the quality of life and the environment”[3]. The eighth plan (1997-2001) primarily was focused on the Thai people. The country wanted to create a balance between the development of the economy, society, and environment. However, a drawback occurred as another economic crisis ensued. The state wanted to restore economic stability in the country. The ninth plan (2002-2006) continued the goals of the eighth plan with the population in mind. The plan promised to improve the economic crisis at the time and sustainable development with the Thai people in mind. The ninth plan was considered a success. The economy of the nation grew 5.7 percent a year on average. Poverty fell, and the quality of life improved for the people. Health insurance covered most of the population from sickness as drug problems decreased.

The Community Forestry Bill was proposed in 1990. The bill outlines the rules local community members must follow when utilizing state-owned forests. The bill was altered six times in the 1990’s to 2000 with intense debates between “community groups, development and conservation NGOs, the Royal Forest Department, and academics”[4]. When it was finalized, a critical aspect included that local communities were allowed to live in the forest if they were able to show that they could conserve it. The local community did not like the idea that the forest management was state-led, so it was changed. The final draft was prepared by an alliance of academics and NGOs, also known as the “people’s version”. This version outlined the ability of local communities to enter use the forests. The people’s version was endorsed by the House of Representatives twice, first in 1996 and again in 2002. Sadly, the Senate rejected the key points of the adjusted proposal and made changes to the bill to restrict the villager’s power to the forests in Thailand. Currently, there has been no agreement between the parties as the years pass.

A main reason why deforestation was high in Thailand for the last century is the growing rural population. Protection policies of deforestation in Thailand has been ineffective due to inadequate attention to the needs of the local people. Deforestation is a way for local Thai communities to meet their basic needs such as food and income. The country has been well known for exporting rice and upland crops to sell to all around the world for profit. Vital concerns on the subject of the exploitation of natural resources are frequently brought forward, particularly on Thailand’s forests. Although many legislations have been brought forward to protect the forests, the intended goals of the legislations were not met on many occasions. Thus, deforestation is a major threat to the future welfare of the Thai people, especially in rural areas. Past management programs have been advocating for state-controlled forests. Local people in forests were posed as threats to the state control of the forests, without considering the reliance of the local communities to the forests for many things, such as food and income. Aside from other natural resources local communities can utilize in forests such as lumber, the amount of water in the local communities is also a key issue. Water is able to supply the local community with electricity, generated locally by hydro plants. During high water levels, the community can utilize electricity all day. During low water levels, electricity is only accessible on Saturdays and Sundays. This is due to the fact that water must be saved up to produce crops, the local communities main source of food and income. Despite the fact that forest loss directly impacts the amount of water in the local community, many communities have continued to log. The reason is that the lumber cut down is able to be used as supplies to build houses. These houses can then be sold to timber merchants for a profit. In many cases, a sale of one small house can equal to one full year of agricultural income.

The Ban Thung Yao Community was established when a group of men and women settled in the area in 1915. There are over 180 families in this community alone. Eight years after their settlement in 1923, the first village chief of Ban Thung Yao declared 9.6 hectares of watershed forest as a protected area to address water shortage problems” [5]. The land in the community is split into three categories; housing areas, agricultural land, and community forest. In the community forest category, there are two subcategories; protected areas, and “areas set aside for the utilization of timber and non-timber products”[5]. The community forest has aided the socio-cultural, economic and environmental development of the Ban Thung Yao Village. The villagers in the community can utilize the forests in the community, however, are unable to mortgage, lease, or sell the land for income. Currently, “the village community forest manages 400 hectares of forestland, with 12 women making up more than a third of the executive committee”[5].

Women in participation of community forestry in the community were assigned to protect “traditional knowledge, wisdom, spiritual beliefs and rituals related to forestry, keeping records of customary laws on forest protection and conservation, and in fund management and often advocated for local ownership of non-timber products”[5]. In addition, they were also involved in forest patrolling and reporting violations to the forest executive community. Men practicing community forestry were focused on hunting for poisonous insects in the forest at night, and exploring new routes and longer trails in the forest”[5]. They also enforced written agreements and laws, particularly on logging, tree cutting in specified areas and forest patrolling. A study into the Ban Thung Yao community showed that women in the community are more knowledgeable about market demand for forest products compared to men. Women who sell vegetables and other items collected from the forest are able to meet the demands of their own household but are also able to generate income by selling these items. Some members of the Ban Thung Yao Village utilize its forest to extract medicinal plants and herbs to set up their herbal enterprises. As doing so, the people in the Ban Thung Yao Community who purchase alcoholic drinks regularly will have an alternative to try to drink herbal drinks. The herbal enterprise has become a major successes the business has become well known nationally in Thailand. The owner of the medicinal enterprise, Ms. Srongporn, began “collaborating with other farmers and non-timber forest product collectors to buy raw materials, as at times the raw materials collected from Ban Thung Yao forest are not enough to meet the market demand”[5].

The Ban Thung Yao community has become one of the most gender equitable community forestry communities in ensuring equal participation from both genders. The community has inspired other local communities in Thailand to have equal gender participation in their communities. This study shows that women in this community are very open to building their knowledge to issues such as “climate change, community-based climate change adaptation, REDD+ and agroforestry”[5]. When developing forest policies, the differing work between men and women in the community should be considered; such as roles, responsibilities, skills, and knowledge in community forest management. Phakee Wannasak is the leader of the women’s group of the local community we are studying in this case study, the Ban Thung Yao village. The women’s group was “established in 1977 by Thailand’s Community Development Department in Ban Thung Yao village, in the province of Lamphun”[6]. When the Royal Forest Department (RFD) announced Ban Thung Yao community forest as a National Park in 1987, the women’s group in the community expressed their displeasure the strongest. Phakee instilled confidence into the other members of the women’s group to resist. In 1989, the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation proposed an annual distribution of $2,455 to the forest in the Ban Thung Yao community. In return, the community forest would need to follow the regulations of the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation. Phakee discussed with the members of the women’s group, and brought out the potential issue of losing rights to the forest and its resources. This would greatly affect the daily life of the community. The women’s group of Ban Thung Yao collectively decided to decline this offer.The Ban Thung Yao Community Forest produces 28 types of wild vegetables, 13 kinds of wild fruit, 25 types of mushrooms, and 20 various kinds of herbal plants. These natural vegetables and fruit total to $30,630, displaying the economic value of the forest. In the present, Phakee is determined to secure the customary rights of the people in the local community and passing it to the next generation. She allocates a large portion of her time towards the younger generation, telling them the history of the Ban Thung Yao Community Forest and the customary beliefs of the people. She wishes that like her, the younger generation of the community can learn from the past to improve the forest in the futureForest products and revenue.

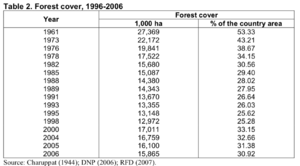

Before the Royal Forest Department (RFD) came into existence in 1896, forest lands were property of the king, rulers of provinces, and landlords. Since the existence of the RFD, all forested areas were owned by the state. The main objective of the RFD was to turn these state-owned forests into money-makers. The RFD will sell concession rights to receive royalties. Since 1989, the RFD needed to adjust their objective into part production, part protection. In the early 1900’s the forest cover in Thailand was over 70%. Thailand had the second fastest deforestation rate in Asia, with Nepal being the fastest.

In 1985, only 29% of forest land remained in Thailand. The North East, East, Central and South regions in Thailand has very little forested land remaining. Northern Thailand has the highest forest cover. However, this is also the same region where deforestation is the highest in the country. Many areas in the North have been logged and have now become grassland. Commercial logging is also a method for government to generate its revenue by way of foreign exchange with other countries. Logging concessions were given to companies to cut timber in the local forests by the government. The government believed that the companies would be able to respect the extraction quotas. However, the concessions did not put the restrictions set by the government into its interests. Deforested areas were left to be regenerated by themselves and were often damaged further by the local communities collecting firewood and agricultural expansion. The government decided to put an end to concessions in 1977 and reduced timber production by 50% two years later. During the 1980’s Thailand grew into a net importer of timber supplies. In 1988, the Royal Thai Government set further regulations after hundreds of villagers were killed in floods and mudslides in Southern Thailand. The main suspected cause of the floods and mudslides was due to the intense deforestation. In 1989, a complete ban from logging was put in place and partnerships between the RFD and logging concessions had formally ended. 15 percent of the total land in Thailand were dedicated towards forest conservation. These areas formerly were committed towards timber production and economic forests. It was during this time where the Thai government understood the dangers of losing forest cover in the country. The dangers of logging in Thailand can be seen by the increased runoff on steep slopes and in watershed areas. This can lead to nutrient depletion and soil erosion. As Thailand loses its forest cover, many animals have become endangered and some even extinct. Areas near the foot of a river, faces the threat of “flooding, sedimentation of water bodies, and decreased availability of water during the dry season”[1]. The idea of forest management has been a tense subject in Thailand. Forest guards and environmental activists have been threatened and/or physically attacked in many areas of Thailand. In some cases, activists have been murdered acting against powerful business people who are in favour of forest exploitation. It is no secret that some government officials are currently involved in illegal logging trade. This is why it may not be in the best interest of the members of the local community to announce their displeasure of logging activities as it will result in a lot of trouble for themselves. The involvement of local communities in policy making has been extremely limited, as most of the policies are decided by the state. When asked about policy making, the local villagers believe that they deserve to be more involved in decision making.

Organizations such as the Royal Forestry Department (RFD) are incapable of developing community forest management, as it faces the weight of state legislations. It is clear that there remains an absence of a national policy to recognize the rights of the community in the local forests. As more communities become involved in managing national forests, we can observe the possibility of community forest management in Thailand. The local community defending their rights against private interests are only able to protect the natural resources if they receive support from the state, legally. The local community does not have economic interest in forest exploitation, but rather economic interest of forest protection. This is an important aspect leading towards sustainable forest management. The practice of Community Forest Management (CFM) will be dependent on the government and the Royal Forestry Department (RFD). One of the reasons why villagers have decided to deforest and use the land for agriculture is the revenue received. The villagers would need to wait for a long time for the trees to grow in comparison where farmers could quickly turn their crops into sales if used for agriculture. If incentives were given to the villagers to manage the forest by the state, the villagers will be more inclined to withdraw the idea of deforestation and using the land for agriculture. Economic incentives should be given to local communities which work to manage their local forest. This will also improve the wellbeing of the members of the local community and improve their ability to manage forests. The 7 major factors preventing people’s involvement in sustainable forest management are “the State’s authorities, centralized management decision-making, inappropriate attitudes towards local people and forest use, lack of trust and strong commitments, lack of knowledge and skills to work with people, non-existent or uncommunicated incentives, and a lack of legal support”[7]. Analyzing data collection in the forest site is effective in changing the forest management operations to fit their needs. Therefore, when the local people interact with the forests, they are able to collect data of the forest, along with their participation in community forest management. Community forest management can generate income for the local community, as well as train the local people to manage natural resources.

Ecological stress between tribal communities, landless farmers, and businessmen has increased as time passed by. We can project that the well-being of the local communities in the future will worsen if the groups are unable to come to terms. Research into local Thailand communities show that men and women are equally knowledgeable and concerned about forest use in their community. Some people find it surprising that men are very encouraging in women’s participation of managing the forest. Most members in local communities are profiled with “insecure land ownership, low incomes, and low levels of education, in a country whose recent economic performances has created soaring expectations of material well-being”[1]. As population grows in communities, resources becoming more limited, and outside business stakeholders, there will be a constant need to overuse the natural resources.The local community faces the dilemma of to use or to not use forest resources. Communities in Northern Thailand can see the advantages of protecting forest resources. However, the people need the resources for food, household needs, and income to improve their daily life. The outlook of the usage of forests have changed immensely over time. In the past, primary role of forests was to produce timber. Local communities now use forests to collect food, fuel, fodder, and construction materials. In some cases, the local villagers also have a cultural and or spiritual attachment towards the forests. To develop a community forest program in Thailand, more power must be given to the local community. The state and powerful organizations such as the Royal Forest Department (RFD) must change their philosophy from a centralized to a more decentralized forest management and forest conservation in order for community forestry to happen in Thailand. Currently, forest in Thailand is managed by a “few high level officials in the national-level committees such as the National Forest Policy Committee, the Wildlife Protection Committee and the National Park Committee”[7]. However, the goals of these committees do not align with meeting the needs of the local communities. In addition, the committees are appointed by political sectors, politicising forest management in Thailand. In recent years, the idea of Community Forestry has grown rapidly in Thailand as the country has been looking for a more sustainable way to manage forests. However, organizations such as the Royal Forestry Department (RFD) and a number of other Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO’s) continue to question the capability of local communities to manage the resources of the forest sustainably. In most local communities, a strong leader is required to lead the community in managing resources in any community forest as the leader ties the members of the community together and represents them in decision-making. Most of the forests in Thailand is state owned, and there is no intention of the state to protect the rights of the local people. Some Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO’s) are working with the local communities to manage forest resources as they act as an intermediary between the forest officers and the local communities.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Flaherty, M. S., & Filipchuk, V. R. (1993, August). Forest management in Northern Thailand: A rural Thai perspective, 263-275. Retrieved October 9, 2018, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/001671859390020I

- ↑ Lakanavichian, S. (2006, February). Case Studies in South and East Asia: Forest Ownership, Forest Resource Tenure and Sustainable Forest Management. Retrieved October 8, 2018, from http://www.fao.org/forestry/10809-09f8870885bd8d85106e0a87cd906b784.pdf

- ↑ Forest Management Bureau, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2009). Thailand Forestry Outlook Study. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/docrep/014/am617e/am617e00.pdf

- ↑ Korpela, E., Bosselmann, A., Kahala, L., Ohtonen, H., Ruotsalainen, A., Sengvue, S., . . . Yli-Hinkkala, M. (2006, January). Community Forestry And Agrofrestry In Thailand- Case Study Of Ban Thung Soong Village Retrieved October 8, 2018, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240623799_COMMUNITY_FORESTRY_AND_AGROFORESTY_IN_THAILAND_-_CASE_STUDY_OF_BAN_THUNG_SOONG_VILLAGE

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Upadhyay, B., Arpornsilp, R., & Soontornwong, S. (2013, August 1). Gender and Community Forests in a Changing Landscape: Lessons From Ban Thung Yao, Thailand. Retrieved October 3, 2018, from https://www.recoftc.org/publications/0000053

- ↑ Upadhyay, B., Forest Heroine: Phakee Wannasak wards off threats to community-led forest governance. (2016, October 30). Retrieved October 2, 2018, from https://forestsnews.cifor.org/21608/forest-heroine-phakee-wannasak-wards-off-threats-to-community-led-forest-governance?fnl=en

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Makarabhirom, P. (n.d.). People’s participation in forest management in Thailand: Constraints and the way out. Retrieved from http://pub.iges.or.jp/modules/envirolib/upload/1503/attach/3ws-15-permsak.pdf

| This conservation resource was created by Gabriel Wan. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |

Photo credit: Michael Cory via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 2.0.