Canada’s Pacific Groundfish Trawl Fishery: Ecosystem Conflicts

The case study involves the B.C. groundfish trawl fishery, which came under attack from ENGOs in the mid-2000s for destruction of the aquatic habitat. Specifically, the ENGOs were concerned with he destruction of numerous coral and sponge species.

The ENGOs were able to give their complaints economic teeth by threatening the industry’s access to major markets. The resource manager, the federal government, was unable to address the problem effectively at the time. The initiative to deal with the problem was taken by the industry, leading to industry –ENGO negotiations. This would never have been possible, if the industry had been unable to act as a cohesive whole. How this intra-industry cooperation was achieved is not yet fully clear. Be that as it may, the negotiations were successful and led to the world’s first habitat bycatch limitation agreement, which came into place in 2012. The case study examines the negotiations and the degree of success of the agreement. It raises the question of the applicability of the B.C. experience to other fisheries in Canada and the rest of the world.

This case study concerns an important component of British Columbia’s commercial capture (wild) fishery, namely consists of the groundfish trawl fishery. The fishery is a complex multispecies one, involving many different species, such as Pacific cod, hake, rockfish and Pollock. There are 70 active vessels in the fleet operating throughout the length and breadth of the British Columbia coast. The vessels employ trawl nets, nets that are pulled through the water by the vessels. The trawls are midwater- pulled through the water column-, and bottom- dragged along the seabed. The bottom trawling activities brought the industry into conflict a decade ago with a group of environmental NGOs (ENGOs), which claimed that the bottom trawlers were doing serious damage to the aquatic habitat. The conflict threatened the long term economic viability of the industry.

Over time, the conflict was resolved in the form a world precedent setting agreement [1]. The agreement was brought about, not through the actions of the official resource managers of the fishery resources, the federal government of Canada, but rather through the initiative of the industry and the relevant ENGOs. This case study investigates the resolution of the conflict. Questions remain as to precisely how this was achieved. Once these questions are resolved, we are then faced with the fundamental question of the relevance, if any, of the British Columbia experience to fisheries elsewhere in Canada, and in the world. It can be asserted with confidence that all of these questions combined will provide the basis for research for many years to come.

Historical Context

Capture fisheries throughout the world are notoriously difficult to manage. The resources cannot be seen directly and are, with few exceptions mobile. The B.C. groundfish trawl fishery is no exception. The management of Canada’s marine capture fisheries is the sole prerogative of the federal government, through the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). From 1980 to 1995, DFO managed the B.C. groundfish trawl fishery through a combination of species by species, season by season total allowable catches (TACs), and licence limitation, which restricted the number of vessels allowed into the fishery. Those vessels allowed into the fishery competed among themselves for shares of the TACs. The management was manifestly unsuccessful.

The competition among the vessels led to the emergence of serious excess capacity, which DFO was incapable of preventing. Several of the TACs were exceeded, year after year. The economics of the fishery was abysmal. Relations between the industry and DFO were adversarial, to say the least. In 1995, the situation had become so grave that DFO took the unprecedented step of closing the fishery.

In 1997, the fishery was re-opened with a new management system, which was not at all popular with the industry. Under the new system, the TACs were divided up among the vessel owners in the form of individual transferable quotas (ITQs). The hope was that the ITQs would eliminate the competition among the vessels. The ITQ scheme was accompanied by mandatory at-sea onboard observers, to be paid for by the industry, and dockside monitoring.

Supporters of ITQs had in the past expressed doubts about the applicability of ITQs in multi-species fisheries because of the complexities involved [2]. In the case of the B.C. groundfish trawl fishery, the ITQ scheme proved to be very successful. Vessel owners had been presented with portfolios of ITQs. The vessel owners quickly became effective portfolio managers, assisted by the fact that a quota market quickly emerged.

The argument has been made that the introduction of ITQs, or other forms of “catch share” schemes will be truly effective, only, if the schemes leads to cooperation among the fishers/vessel owners [2]. The argument is based upon the theory of strategic interaction, more popularly known as the theory of games. There are two broad categories of games, competitive and cooperative, as well as blends between of the two. Competitive games can be seen to lead to undesirable outcomes, much evident in fisheries. The B.C. groundfish trawl fishery in the mmid-1990s was an example of a particularly destructive fisher competitive game. Hence the argument re-expressed is that ITQs, or other forms of “catch share” schemes will be truly effective, only if they succeed in transforming a competitive fisher game into a cooperative one.

Cooperative games, however, are always under threat from “free riding”, in which “players” (agents) defect and enjoy, at no cost to themselves, the benefits of cooperation of the non-defectors. If “free riding” becomes extensive, the cooperation will break down, and the cooperative game will degenerate into a competitive one. The greater the number of “players” (agents), the greater the threat of free riding.

Many economists, who are supporters of ITQs, have argued that the scope for effective cooperation among ITQ holders is very limited, because of the free riding problem. One economist, viewing ITQ history, has put the maximum number at 15 [1]. The vessel ownership relations in the fishery in question is complex, but it has been estimated that the number of independent “players” in the industry is not fewer than 30. Moreover, as noted the fleet operates throughout the length of the B.C. coast, making monitoring of the vessel owners of one another almost impossible [1] .

Effective cooperation did, however, emerge within the industry. The full explanation of why this occurred has yet to be given. It has been speculated that string surveillance and enforcement by DFO played a key role [1]. This has yet to be proven, however.

The industry does have an association, the Canadian Groundfish Research and Conservation Society (CGRCS). It must be noted, however, that the CGRCS is an association, and nothing more. It exercises no control over individual members.

The industry, a cohesive whole by the 2000s was to be faced with a new problem, in the middle of that decade, which could have threatened its survival. The problem arose from the bottom trawling segment of the industry and the charge of habitat destruction.

Framing the Problem

- Describe a (hypothetical or actual) problem or dilemma related to sustainability or environmental ethics, describe why it is a problem and why it is difficult to solve

The waters off British Columbia have extensive “groves” and “forests” of sponge and coral. Scientists argue that the sponge and coral play important ecological roles. For example, they “provide substrate for egg cases, attachment platforms fro sedentary invertebrates, shelters from predators, and energy –conserving refuge from water currents” [1]. The bottom trawlers were seen as being as destroyers of these “groves” and “forests”. Several environmental NGOs (ENGOs) mounted attacks, e.g. the David Suzuki Foundation, World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF).

Economists are fond of using the term negative externalities, in which an individual, firm industry, country imposes costs on others that are not borne by the individual, firm industry, country. The B.C. sponge and coral case provides an excellent example. The destruction of the sponge and coral imposed a cost on society as a whole, but imposed no cost on the trawling industry. The sponge and coral have no commercial value, therefore the industry had no interest in conserving the sponge and coral resources.

The problem when confronted with negative externalities is to find ways of “internalizing” the externalities, i.e. of ensuring that these costs are borne by those creating the costs. The ENGOs succeeded in doing this. Most of the product of the industry is marketed along the Pacific coast of North America. California is an important market. In California there exits the Monterey Bay Aquarium, which has a powerful interest in aquatic conservation. Through its Seafood Watch program, it identifies fisheries as sustainable or unsustainable. The Seafood Watch program is listened to by major food retailers and restaurants. The complaints of the B.C. ENGOs came to the attention of the Monterey Bay Aquarium. The threat of blacklisting by the Monterey Bay Aquarium quickly internalized the externality.

Aggravating the problem for the industry was the fact that, while DFO was aware of the problem, it lacked the legal power to address it. The key piece of fisheries legislation in Canada is the Fisheries Act. A court case in 2004 led to the conclusion that prohibitions against destruction of the habitat did not apply commercial fishing [1]. The lack of legal power is being addressed, but it will take time. The industry did not have time.

The industry had the motivation to address the problem, but the motivation was a necessary, but not sufficient, condition. The motivation had to be accompanied by the industry’s ability to act as a cohesive whole. This the industry had, for reason’s that are not sufficiently understood. The work now began towards developing a solution.

Using the vehicle of its industry association, the CGRCS, the industry approached a consortium of ENGOs to see, if a negotiated solution could be considered. The ENGOs responded positively. Support from DFO had to be obtained, of course. DFO was pleased to give the initiative its blessing and support. Negotiations commenced, with the shared objective of gaining Monterey Bay Aquarium/Seafood Watch seal of approval. Let it be stressed that the initiative came from outside government, from industry and ENGOs.

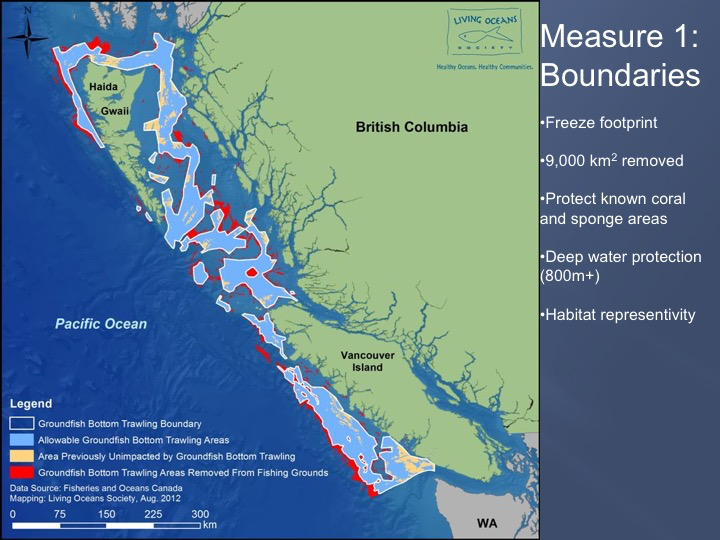

During the course of the negotiations extensive mapping of the coast took place, involving the cooperation of the ENGOs, DFO and the industry, with the objective of identifying “hotspots”. The “hotspots” were declared off limits by DFO. In addition to this, an encounter protocol was developed. Any vessel hauling in more than 20 kg of coral/sponge had to report to an ENGO/industry protocol committee. Clusters of such hauls would lead to an area being declared a “hotspot”. As a result of this mapping, and identifying “hotspots”, the area open to bottom trawling was reduced by approximately 22 per cent ([1]).

At the same time, an agreed upon limit to the capture of coral/sponge had to be agreed upon. The limit, the global industry quota had to be low enough to ensure the safety of the coral/sponge, but not so low as to cause the industry to seize up. On the basis of historical data and scientific evidence an agreed upon annual industry quota was set at 4,500 kg. of all coral and sponge. It was further agreed that the goal would be to reduce the quota over the long run to just under 900kg. [1].

The global quota had to be distributed among the vessels of the fleet. The scheme of ITQs plus at sea observers proved useful. The 4,500 kg. was divided up among the vessels under a pre-agreed formula like very small ITQs. Any vessel that exceeded its coral/sponge quota, and was unable to cover the “overage” by buying or leasing quota from other vessels, had to cease fishing for the remainder of the season [1].

The agreement, the British Columbia Groundfish Trawl Habitat Conservation Collaboration Agreement was signed in February 2012, and was formally implemented by DFO in early April of that year. The negotiators of the Agreement maintain that this is the first habitat bycatch limitation agreement in the world [1].

Has the Agreement shown signs of success, or is it encountering difficulties? The groundfish trawl fishery season comes to a close in the third week in February. The Agreement’s first year ended on February 20th, 2013. The reported catch of coral and sponge by the industry over the year was 500 kg. – well below the long term goal of just under 900 kg., let alone 4,500 kg. Since that time, the annual industry catch of coral and sponge has declined further. The third week in February 2016 marked the end of the fourth year of the Agreement. The reported catch of coral and sponge by the industry over the fourth year was 280 kg. (Bruce Turris, personal communication).

The Agreement, its development and results so far, were written up and published in the journal Marine Policy, in October 2015. The article had six authors, three from ENGOs, two from industry, along with one academic. In February 2016, the six authors were the joint recipients of the Vancouver Aquarium and Coastal Ocean Research Institute 2016 Murray A. Newman Conservation Action Award.

Political

- Describe governmental jurisdiction over this issue and dilemmas for lawmakers, current laws/precedents related to the problem

Economic

Economists stress the fact that, when looking at the net economics benefits produced an industry, region, country, non-market as well as market benefits must be included. The coral and sponge in question produce non-market benefits to society, in contrast to the finfish being caught by the industry. To economists, the relevant fishery resources plus coral and sponge must be seen as assets to be managed with the objective of achieving the maximum economic return to society over time. The management should be seen as the management of a portfolio of assets. What counts is, not the economic returns on individual assets, but is rather the economic return on the portfolio as a whole. It can be argued that a decade ago, when the coral and sponge were more or less being ignored, the “portfolio” was not being managed optimally.

The Agreement and its results, while encouraging, leave several questions unanswered. These are:

I. No agreement would have been forthcoming, if the industry had not been acting as a cohesive whole. This was achieved, even though the ITQ holders acted as individuals. The achievement of this cooperation has not been satisfactorily explained. As noted by Wallace et al. [1], many economists, who are strong supporters of ITQs, would have argued that the cooperation achieved by the industry should have been impossible. How in fact was this intra-industry cooperation achieved? Much more research is required, bringing to bear the theory of strategic interaction.

II. The answering of this question leads to an ancillary one. Are ITQ schemes the sine qua non for the achievement of such cooperation? Very unlikely, but once again more research is required.

III. Following on from all of this is the big multi-part question of the relevance of the British Columbia experience to the rest of the world. Must the experience be seen as unique to British Columbia, or is it applicable to Atlantic Canada, and to other fishing states? If it is applicable to other fishing states, is it applicable to developed fishing states only, or can it be applied to developing fishing states as well, and, if so, to what degree? Answering this big question will take years of research.

Case study references

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Wallace, S., Turris, B., Driscoll, J., Bodtker, K., Mose, B., & Munro, G. (2015). Canada's pacific groundfish trawl habitat agreement: A global first in an ecosystem approach to bottom trawl impacts. Marine Policy, 60, 240-248. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2015.06.028

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bjørndal,T and Munro,Gordon(2012). The Economics and Management of World Fisheries. Oxford University Press.Volume: 28 (3), 305-306. Retrieved from: http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=http://gw2jh3xr2c.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=sersol&SS_jc=TC0000834488&title=The%20economics%20and%20management%20of%20world%20fisheries

Additional resources

- Research Paper from the David Suzuki Fundation- Government of Canada, Integrated Fisheries Management Plans. Retrieved on 19th May, 2016 from: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fm-gp/peches-fisheries/ifmp-gmp/index-eng.htm

- Government of Canada Resources on Integrated Fisheries Management Plans: Government of Canada, Integrated Fisheries Management Plans. Retrieved on 19th May, 2016 from: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fm-gp/peches-fisheries/ifmp-gmp/index-eng.htm

- How would a social scientist approach responding to the problem outlined in this case study, and what are some responses they might offer?

Who are the rights holders? Involved constituency groups?

Authors like Diane Newell, Fisher, Elaine Pinkerton and Cole Harris have researched and written about the Co-Salish Sea region and the dependence of the coastal First Nations on species included in this case study. Students might look at: (a) the degree of involvement of FNs in the industry grouping and (b) the historic treatment of First Nations rights to marine resources.

Another constituency group is the Provincial Department of Fisheries which is known to have an adversarial relationship with the Federal Department of Fisheries. How is the Province of BC involved? And, if not significantly involved, what are the implications and repercussions?

- What elements of the case would they be most likely to focus on and why?

Social science students might consider:

- who holds power, who is at the table and who is not when these decisions are taken and monitored. In other words, is this a robust multi-stakeholder process? Why are the commercial fishers and the Federal Government of Canada the main players?

- who wins and who loses?

- What kinds of questions would they ask?

- What kinds of disciplinary approaches or methodology might they use?

Students might approach this case study from a political ecology approach which pays attention to asymmetries in power, to governance across scales and to which narrative discourses are dominant.

How would a legal scholar approach responding to the problem outlined in this case study, and what are some responses they might offer?

Interesting in that the case seems to exist outside the scope of existing BC Fisheries legislation 2004 (point made by the author) - so the problem is not so much one about existing legal rights but rather a form of negotiated agreement. It is perhaps a dimension of ADR (alternative dispute resolution). Would probably focus upon the actual terms of the agreement and reflect on the enforceability of it. Wonder if it has applicability outside BC because the matter seems to go towards a lack on the part of resource management - can we presume that other jurisdictions will (a) have the same gap in legislative or planning authority powers (b) if there is a gap will the authorities in such jurisdictions be willing to accede to a separate independent agreement (c) there is the same combination of negative externalities that give the power to the ENGO to engage with the industry to compel or induce engagement?

- What elements of the case would they be most likely to focus on and why?

The rights and interests created by the agreement - how they stand in relation to the rights of the parties and their ITQ. What do you do if one party to the agreement breaches their part of the undertaking? (Is this part of the agreement? If it is, then is the enforcement provision legally enforceable)

- What kinds of questions would they ask?

What happens if a party fails to comply with the obligations - is it enforceable?

- What kinds of disciplinary approaches or methodology might they use?

Examine the regulatory mechanisms that exist in different jurisdictions and how they have dealt with comparable problems (e.g. Australian Fisheries Management Authority).